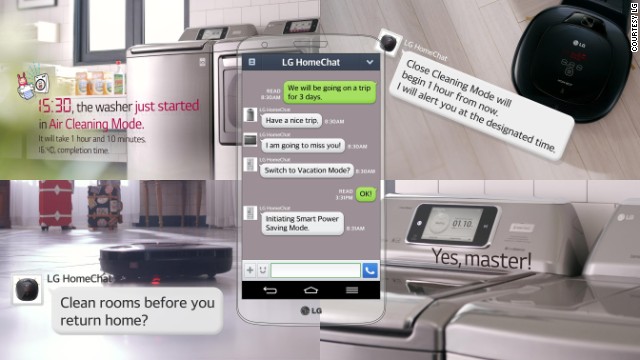

Exciting or frightening,

these connected devices of the futuristic "smart" home may be familiar

to fans of science fiction. Now the tech industry is making them a

reality.

Mundane physical objects

all around us are connecting to networks, communicating with mobile

devices and each other to create what's being called an "Internet of

Things," or IoT. Smart homes are just one segment -- cars, clothing,

factories and anything else you can imagine will eventually be "smart"

as well.

But there's a catch: So

far, most Internet of Things products have been a messy tangle of

different wireless protocols and brands. Many can communicate with their

own apps and ecosystems but haven't found a way to play nice with each

other. The Nest thermostat, which can adapt to your energy-consumption habits, is just one example.

These standalone devices

and ecosystems are running their own proprietary software and speaking

different languages. Your smart toaster is humming along in French, for

example, while your fridge is babbling about dairy expiration dates in

Japanese.

Google's plan for world domination

Google's plan for world domination

Now chipmaker Qualcomm is

trying to give the industry a major push with an open-source project

that can link all these disparate pieces. Qualcomm is hoping its platform, called AllJoyn, could act as a sort of universal translator for the industry.

Over the past four years,

Qualcomm has been working on its AllJoyn protocol to connect devices

from different manufacturers, even if they have different communication

standards. It wants to be the de facto language your fridge, lightbulbs

and garage door all use to communicate.

"The only way that vision

can be realized is if we turn this into a true panindustrial effort

with companies all over the world," said Liat Ben-Zur, Qualcomm's senior

director of product management.

Choosing a standard

Many standards already

help smart devices communicate, though none has emerged as a dominant

option yet. Some companies, such as SmartThings, Lowes and Revolv, depend on a physical hub to link devices.

Experts say this market

will struggle to really take off until someone can convince the major

players it's in their best interest to work with other brands.

"We could see a few

large ecosystems emerge for (the Internet of Things), such as we have

today with Android, iOS and Windows. But consumers like to have choices

and will demand that closed systems learn to communicate with each

other," explained Karen Bartleson, president of the IEEE Standards

Association.

If there are too many

different ecosystems, people will find a way to connect them -- much

like how the problem of multiple phone chargers is being solved by

micro-USB, she said.

"Because (the Internet

of Things) is so vast and varied, it will be hard to come up with a 'one

size fits all' standard," said Bartleson. "Instead of a single,

dominant communication standard for IoT, there will likely be several

that serve different purposes."

A company with as much

industry clout as Qualcomm might have luck bridging some of the gaps.

It's a smart business move: The wireless technology giant makes many of

the chips found in smartphones and tablets. It also sells the chips that

will go inside smart thermostats, security systems, cars and everything

else.

But the connected-things

revolution will only work if all the companies and products find a way

to break out of their silos and work together, according to Ben-Zur.

"Oftentimes we kind of

think about the evolution of the Internet in two revolutions. The first

revolution was the connected Internet," she said. "The second kind of

revolution was when we suddenly went to the mobile Internet."

Being able to access the

Internet from our pockets isn't just revolutionary because it is

portable. The devices collect and share information about us using

built-in sensors, such as accelerometers and GPS. The Internet becomes a

two-way street where we share context about our location, environment

and habits so it can serve up customized information.

A third revolution

Ben-Zur predicts the

Internet of Things will be the third revolution. Sensors will show up in

more and more devices and turn them into sponges that soak up data

about our habits, environment, movements and health.

A smart smoke detector,

for example, might also gather information about the pollen count in a

house. A home security system's motion detectors can track a family's

movements and location over time, sharing information with a central

heating or cooling system to customize each room's temperature.

But it's still to early

to say for sure how all these devices will chat with each other and

whether Qualcomm's AllJoyn or some other option will take off.

The exact killer apps

for the Internet of Things are also a mystery. We won't really know how

the technology will change our lives until we get it into the hands of

creative developers.

"The guys who had been

running mobile for 20 years had no idea that some developer was going to

take the touchscreen and microphone and some graphical resources and

turn a phone into a flute," Ben-Zur said.

The same may be true when developers start experimenting with apps for connected home appliances.

"Exposing that, how your

toothbrush and your water heater and your thermostat ... are going to

interact with you, with your school, that's what's next," said Ben-Zur.

0 comments:

Post a Comment